The below should be considered as general market commentary and does not constitute investment advice. You should always seek advice from your independent financial adviser before making investments.

So, now we are in Q4. Smart investors took the bearish sentiment at the end of September to sell out and book losses, ensuring that S&P500 ended Q3 on a 2022 low of 3585 – more than 25% down since the start of the year.

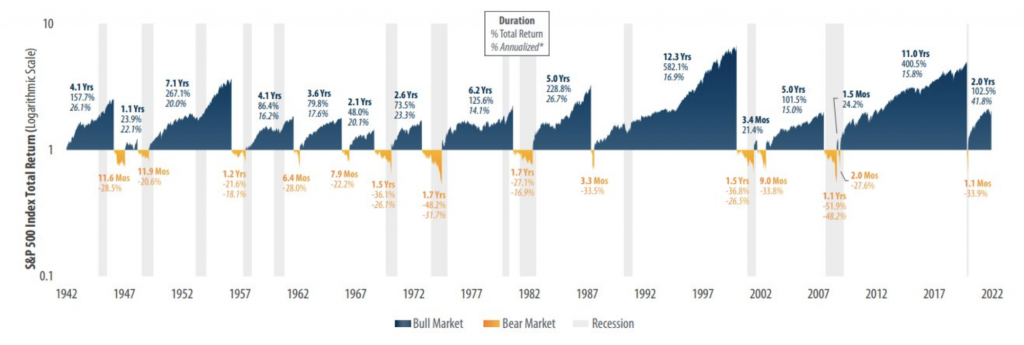

Yep – we are officially in a bear market. We’ve had 15 bear markets since 1942 (including this one). This means that the bear has come out once every 5.5 years. The last bear market in 2020 was barely a one-month blip (albeit with steep losses as the covid panic engulfed markets). However, on average, bear markets between 1942 and 2022 had a duration of 11.3 months and led to losses of 31.7%.

So far, the 2022 bear market has lasted a little over nine months and measured a 25% drop from peak to trough. So not far off the place where bear markets have historically bottomed out. And some commentators have suggested that it might soon be time to reenter markets.

And indeed, following September’s clearing-out, we started October and Q4 with a bang. Once investors had sold shares and booked losses at the end of September, many investors felt it was time to pile back in. As a result, the start of the new quarter has been buoyant, with the bellwether S&P500 index up 5% in the first few days of trading. However, the index gave up most of those gains by the end of the week, and it looks like we may not have touched the bottom quite yet.

Indeed, several factors suggest that this bear market might still have some life in it.

Demand crunch

On the demand side, there is a looming interest rate crunch coming to mortgage owners everywhere – especially if you are on a variable interest rate.

US mortgage rates have now jumped to a 16-year high, putting pressure on new home construction and leading to lower construction sector activity.

Furthermore, about 11% of US mortgages are variable, representing about 19% of the total value. Interest hikes flow through to disposable household income, meaning less demand in the quarters ahead.

On the UK side of the pond, we are in for another shellacking. Here, about 20% of mortgage borrowers are on variable rates. Moreover, 40% of fixed-rate mortgages expire at the end of 2022. This means that by Q1 2023, 60% of the UK’s homeowners will be at the mercy of the massive recent spike in interest rates.

So homeowners need to spend much more on servicing their mortgages. In addition come price hikes on energy, groceries and other goods. This means that homeowners and consumers, in general, are facing a challenging macroeconomic climate.

Supply-side crunch

It’s not just consumers that are facing challenges. In the US, the Labour’s share of GDP is at a historic low. On the other side, corporates’ share is at a historic high. But this level is unlikely to persist in light of the following trends:

- Geopolitical risks mean that corporates are reversing offshoring. World trade as a % of GDP has already dropped from nearly 60% in 2011 to 56% in 2019, with expectations of further declines as more corporates are reshoring manufacturing. This adds resilience but also increases costs.

- At the same time, the proportion of the population that is of a working age is shrinking. This tips power back towards employees – something we have started seeing materialise in the form of strikes (that invariably will lead to higher labour costs).

So at the same time as demand is likely to contract, the corporate cost base is being put under pressure. All else equal, we expect this to put earnings under further pressure.

Unwinding QE

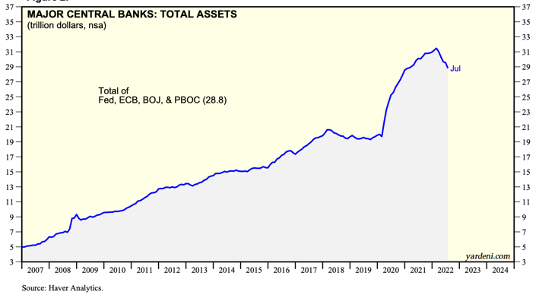

As of the start of 2022, central banks across the world had amassed $31trn of assets as part of the various quantitative easing programmes. It is a staggering amount. The QE programmes are now being reversed, and the expectation is that this reversal will continue. In many ways, quantitative easing was instrumental in inflating asset prices over the past decade+. The expectation is that QE reversal will put asset prices (including equities) under pressure).

Geopolitical risks

Finally, there are still real tail risks from e.g. the war in Ukraine – particularly Putin’s threat of using tactical nuclear weapons. While the expected probability of a strike still is relatively low, the implications for investments and equities would be significant.

So overall, it looks all but certain that we’ll see recession rear its head in 2023 and that equities will be put under continued pressure.

Given all of this, it seems premature to rush back into the markets at this point.

The question then becomes, how far are we from the bottom?

Some commentators have suggested that the summer of 2023 is when markets will have bottomed out, and it’s time to get back on board the equities train. It’s worth bearing in mind that stock markets usually are ahead of the recessionary curve. Historically, the S&P has hit its high seven months before the start of a recession. Conversely, it typically bottoms out four months before the end of a recession. In other words, if you think the recession is over by next summer, Q1 might be the right time to start moving back into equities.

How to think about venture capital during a bear market?

The pullback in public markets has made many investors reevaluate their venture capital allocations. If listed equities are going through a tough time, will small tech companies be facing the same (or worse)?

However, it turns out that small tech startups play by entirely different rules to listed behemoths. There are many reasons for this, some of them being:

- B2B tech companies typically help their customers save money. And that’s something everybody is looking to do in a tough economy;

- Tech startups often compete in small and less congested market segments, meaning that their performance is tied more closely to individual deals and much less to the macroeconomy. Small teams that execute well are great at finding ways to retain and grow revenue, even if macro-trends are contractionary; and

- Startups often pursue opportunities tied to new technologies, regulation changes or other factors giving tailwinds. This means that while the macro-factors can be contractionary, startups can still find ample boost through micro-factors.

Growth-stage unicorns have been the exception during the last few years. These companies have stayed private even after their valuation has hit multiple $bn. In many ways, the performance of unicorns has been closely tied to public market equities, as their size and shape are much closer to that of a listed company (with a higher cost base and lower growth) than an agile, early-stage startup.

A few years ago (before “New Venture” and the unicorn economy), Invesco published this whitepaper showing no correlation between venture capital and large-cap equities:

So rather than seeing the current market as a reason to pull back from venture capital investing, venture capital should be seen as a powerful way to add uncorrelated diversification to investors’ portfolios. Because, as we know, Diversification is the only free lunch in finance!